Sia Load Test Wrap-up

Over the past three months, I performed a series of load tests on Sia. I published reports to describe each test individually, but now I’d like to look back on the tests at a high level to share what I learned about Sia and how to improve testing as the project moves forward.

Result summary

| Metric | Worst-case | Real data | Best-case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total uploaded (file bytes) | 47.2 KiB | 4.3 TiB | 1.5 TiB |

| Total uploaded (absolute bytes) | 9.8 TiB | 15.4 TiB | 7.2 TiB |

| Storage efficiency | 0.0000004470% | 28.3% | 21.5% |

| Total files uploaded | 48,358 | 2,626 | 40,552 |

| Total file contracts created | 60 | 62 | 68 |

| Total spent | 3625 SC $50.75* USD | 4377.1 SC $61.07* USD | 1,840 SC $25.21* USD |

| $ per TB/month** | $350 million | $4.51 | $5.13 |

| Total test time | 596.8 hours (24.9 days) | 231.7 hours (9.7 days) | 336.0 hours (14.0 days) |

| Average upload bandwidth (file data) | 0.00000018 Mbps | 45.8 Mbps | 11.2 Mbps |

| Average upload bandwidth (absolute) | 40.3 Mbps | 162.1 Mbps | 52.2 Mbps |

| Sia crashes | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* Based on Siacoin value at test start. Assumes that unused renter funds will successfully return to the test wallet at the conclusion of the renter contracts.

**Assumes that a standard renter contract lasts 2.77 months. Excludes bandwidth costs. Includes all fees.

Test environment

- Sia version: 1.3.1

- OS: Windows 10 x64

- CPU: Intel i7-5820K @ 3.3 GHz

- RAM: 32 GB

- Local disk (for Sia metadata): 512 GB SSD

- Network storage (for input files): Synology DS412+ (4 TB free)

- Internet connection: Verizon FiOS home - 940 Mbps download / 880 Mbps upload

What I learned about Sia

Sia is robust

I’ve been using Sia for almost two years now. I like to push Sia’s limits and run it under weird scenarios, which means I’ve seen plenty of Sia crashes over the years.

Sia didn’t crash once during these tests. Cumulatively, Sia ran for 48.6 days and processed 91,536 files without a single crash.

Anecdotally, most of the crashes I see others reporting lately relate to memory exhaustion. In my load test, Sia was running on a system with 32 GB of RAM, so memory was harder to exhaust. In addition, the test script limited Sia to five simultaneous uploads, which may have kept memory demands in check.

Storage isn’t that cheap

Sia has always touted low storage costs as one of their competitive advantages. The Sia website has for the past few years listed storage costs as $2 per TB/month, claiming this is 90% less expensive than incumbent providers.

I found that, after taking into account Sia’s fees and extra costs from replication, Sia remains low-cost, but the savings are not as dramatic as advertised.

The test with the best cost efficiency was the real data test, which achieved $4.51 per TB/month. This is certainly lower than Amazon S3’s standard storage class ($23 per TB/month), but the comparison to S3 isn’t quite realistic. AWS doesn’t have an offering that’s similar to Sia in performance. Standard S3 is much more performant than Sia, whereas Amazon Glacier is much less performant.

Google Cloud Storage’s (GCS) nearline storage class is probably the closest comparison in terms of performance. It’s $10 per TB/month, so Sia still undercuts it by half. Still, there are low-cost centralized providers like Backblaze and Wasabi that offer storage for $5 per TB/month, which is on par with Sia.

| Sia | Amazon S3 (Standard) | GCS Nearline | Azure | Backblaze B2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage cost (per TB per month) | $4-5 | $23 | $10 | $18.40 | $5 |

I’m excluding costs for this comparison that I consider negligible:

- I exclude the frictional costs of acquiring Siacoin.

- To use Sia, the user must convert fiat currency to a mainstream cryptocurrency such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, then trade that cryptocurrency for Siacoin. Each conversion and coin transfer incurs a small frictional cost.

- I exclude per-request costs.

- Some traditional providers charge fees per HTTP request, but these charges generally account for <1% of costs in practice.

Upload bandwidth is inexpensive

One surprising result was the low cost of upload bandwidth. For the real data and best-case tests, upload bandwidth was around $0.40-$0.70 per TB of file data uploaded.

This isn’t exciting in itself because cloud providers typically charge zero for inbound data transit. It does, however, bode well for download bandwidth costs. I didn’t measure downloads in this test, but if they’re within even an order of magnitude of upload bandwidth, it would give Sia a huge price advantage over traditional storage providers, most of whom charge a premium for bandwidth:

| Amazon S3 (Standard) | GCS Nearline | Azure | Backblaze B2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Download cost (per TB) | $90 | $130 | $90 | $10 |

Cost accounting is unreliable

Sia reports its spending through both its renter and its wallet APIs. Unfortunately, they contradict each other.

In each test, the wallet APIs reported that Sia spent money, but the spends didn’t match up with purchases that the renter APIs reported:

| Test case | Spending according to /renter/contracts | Spending according to /wallet | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worst-case | 2,966.7 SC | 5,000.0 SC | 2033.3 SC |

| Real data | 2,866.7 SC | 5,000.0 SC | 2,133.3 SC |

| Best-case | 2,833.3 SC | 3,200.0 SC | 366.7 SC |

For the purposes of my reports, I treated the wallet APIs as the ground truth for spending.

Sia also reports spending metrics that are logically impossible. In each of the tests, Sia’s accounting showed increases and decreases in total storage spending over time. When Sia spends money on a storage contract, the expenditure is permanent so total spending should never decrease.

Cost estimates are wildly inaccurate

Sia offers a /renter/prices API that Sia-UI and the command-line client use to provide cost estimates to the user before they store data on Sia. I found that its estimates drastically underestimated Sia’s costs in practice:

Real data scenario

| Cost | Advertised | Actual (corrected accounting)* | % difference from advertised cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upload (SC/TB) | 27.7 | 35.2 | +27.4% |

| Storage (SC/TB/month) | 96.5 | 203.5 | +110.8% |

| Contract fees (SC) | 56.2 | 1,117.3 | +1,888.1% |

* Scaling Sia’s reported costs by 1.74x to correct for accounting bugs.

Best-case scenario

| Cost | Advertised | Actual (corrected accounting)* | % difference from advertised cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upload (SC/TB) | 37.1 | 53.1 | +43.2% |

| Storage (SC/TB/month) | 99.1 | 188.2 | +90.0% |

| Contract fees (SC) | 70.0 | 710.0 | +914.9% |

* Scaling Sia’s reported costs by 1.13x to correct for accounting bugs.

To work around Sia’s previously mentioned accounting bugs, I treated Sia’s wallet API as authoritative and scaled the numbers from its renter API by a constant factor to match. So in the case of the best-case scenario test, the renter reported 2,866.7 SC in total spending, while the wallet reported 5000 SC in total spending. I treated the wallet as correct and scaled the subcomponents of the renter cost by 5000 / 2866.7 = 1.74x to reconcile the difference:

| Cost | Raw | Corrected |

|---|---|---|

| Upload | 94.3 SC | 164.1 SC |

| Storage | 1,508.8 SC | 2625.3 SC |

| Fees | 640.6 SC | 1114.6 SC |

| Unused contract funds | 622.9 SC | 1083.8 SC |

| Total | 2,866.7 SC | 5000 SC |

Sia-UI has a separate price estimation bug that exacerbates the incorrect estimates from the API. Sia-UI takes the incorrect prices from the renter API and performs an incorrect calculation to give an even more inaccurate estimate of costs on the network.

Costs are complex and unpredictable

In addition to Sia’s inaccurate estimates, its costs are so complex and depend on so many unknown factors that it’s impossible to calculate costs in advance.

On storage providers like S3 or GCS, you can predict costs pretty accurately with the following formula:

total_cost = (file_size * upload_cost) +

(file_size * storage_cost) +

(file_size * download_cost)

I’m neglecting per-request costs and maybe a few other minor costs, but that formula gets you to within 5% of your actual bill. All variables are known a priori.

Now, I’ll try to create a formula for estimating costs on Sia:

contract_size = file_size * (1 / storage_efficiency)

total_cost = (contract_size * upload_cost) +

(contract_size * storage_cost) +

(file_size * download_cost) +

((contract_count + contract_renewals) * contract_fee)

Already, it’s more complex than with traditional providers.

The worst part is that so many of the variables are unknown. There are nine different variables in that formula. The user only knows one in advance: file_size. If Sia fixes their price estimation bugs, four more variables can be known ahead of time: upload_cost, storage_cost, download_cost, and contract_fee.

For the rest of the variables, the user can’t know the values in advance even if Sia provided 100% accurate price estimates. storage_efficiency depends on the distribution of file sizes in the user’s data, and how stable their hosts are. Sia can’t predict it without looking at the files or knowing when hosts will go offline.

contract_count and contract_renewals depend on the stability of the hosts and on the user’s storage activity. If the user downloads their files frequently, they will generate more contract renewals than a renter who uses Sia for cold storage and rarely downloads files. Even if the user knows what their usage pattern will be, they still can’t predict their number of contracts because of Sia’s opaque and confusing contract purchasing logic.

Fees represent a high proportion of cost

Before I ran this test, I assumed that fees would be only a small percentage of total costs, like 2-4%. In reality, fees accounted for 29-44% of costs in these tests.

As explained above, fees are the cost for which Sia makes the poorest predictions. In these tests, fees were 10-20x more than what Sia’s price API predicted. As a result, fees make up a substantial share of total costs:

| Test case | Fee spending (incorrect accounting) | Total spending (incorrect accounting) | Fees as % of total spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worst-case | 697.6 SC | 1,593.1 SC | 43.8% |

| Real data | 640.6 SC | 2,243.8 SC | 28.5% |

| Best-case | 628.6 SC | 1,473.3 SC | 42.7% |

Note that for these numbers, I’m using the raw numbers from the renter APIs even though I think they’re incorrect. The relevant metric is fees as a percentage of total costs, which remains the same even if I scale all the numbers by a constant factor to reconcile Sia’s accounting errors.

Fees are variable, not fixed

Prior to this test, I thought that contract fees were independent of the value of the contract.

Using Bitcoin, a 1 BTC transaction costs the same in fees as a 10 BTC transaction. I believed that Sia’s contract fees would similarly be the same on a 500 SC Sia renter allowance as a 5000 SC allowance. Both Sia-UI and the /renter/prices API make that claim: you pay the same flat fee regardless of allowance amount. This is not true.

Before I began official testing, I did a practice run of my test script using a 500 SC wallet. When I began the real tests with a 5000 SC wallet, I was surprised to see Sia spend almost four times in contract fees as it did for my 500 SC test.

As the test progresses, Sia’s accounting becomes unreliable, but at contract formation time, Sia’s numbers are consistent and credible. Comparing the 500 SC test to the 5,000 SC test, there are clearly big differences, both in absolute fees and in fees as a percentage of total spending.

| Allowance | Contract fees (contract creation time) | Total contract spending (contract creation time) | Fees as % of contract costs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 SC | 122.5 SC | 166.7 SC | 73.5% |

| 5000 SC | 454.4 SC | 1666.7 | 27.3% |

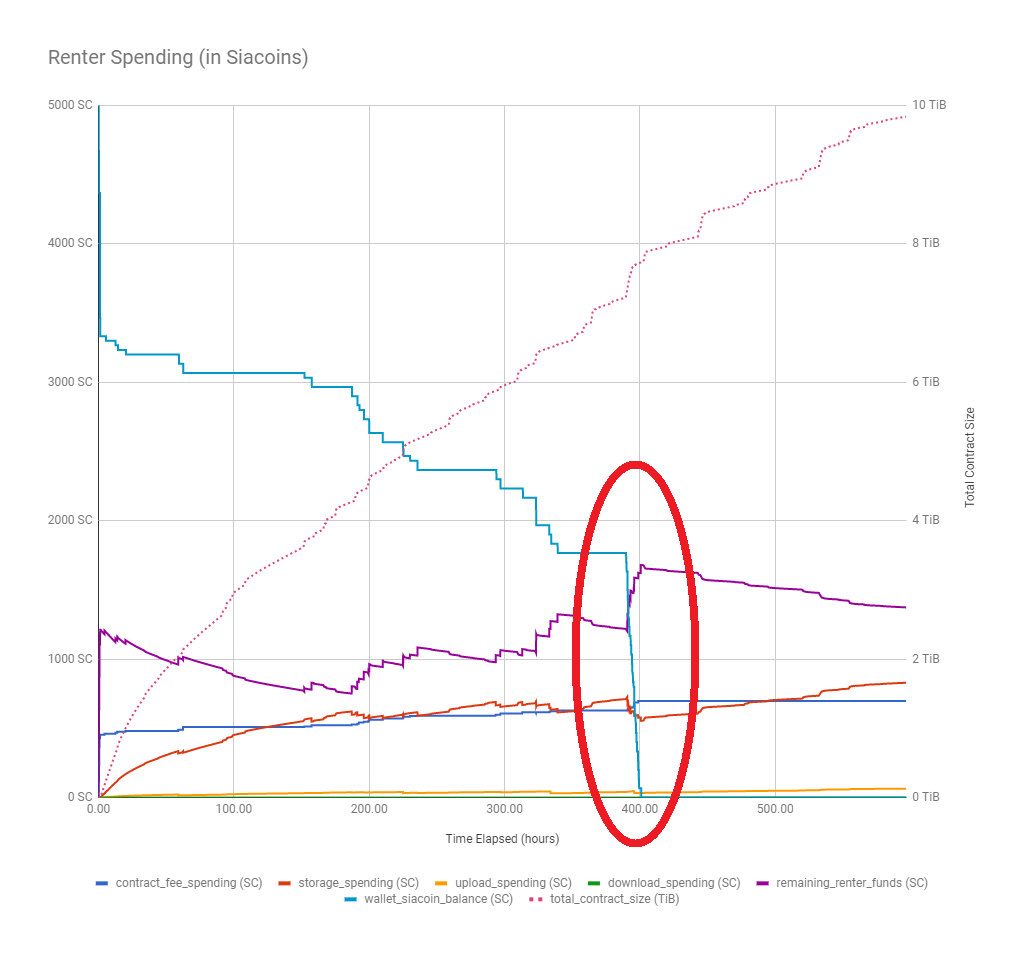

Contract spending is unintuitive

This test showed me that my mental model of Sia’s contract management was incorrect. I thought that Sia purchased 50 contracts for the duration of the contract period (12 weeks, by default) and then used these 50 contracts until the funds were exhausted or the associated hosts went offline.

This is not how Sia manages contracts. I don’t fully understand what Sia’s contract logic is, and I don’t see the behavior documented anywhere, but I can glean a bit from the test results.

Sia seems to optimize for high upload bandwidth at the expense of higher costs. When the user sets an allowance of 5000 SC, Sia doesn’t spend 5000 SC on contracts. Instead, it spends 1/3 of the allowance on contracts and keeps the remaining 2/3 on reserve to reinvest in hosts that perform well.

When Sia finds a host with high bandwidth, it renews contracts with that host well before its other contracts are exhausted. This is problematic because Sia always renews by the same small, fixed amount, and small renewals result in a higher proportion of fees. Correction: Sia actually doubles the contract size each renewal, so only the first two renewals are the same size.

There’s a lot about Sia’s contract purchasing that I still don’t understand. I’m unclear about what causes Sia to purchase a contract with a new host rather than renewing with one of its existing hosts. And I don’t know how Sia chooses between spending extra on fast hosts or spending funds already allocated to slower hosts.

Puzzlingly, Sia sometimes renews contracts before the contract’s funds are even close to exhaustion. Sia renewed a contract in one test to 133.3 SC in increments of 33.3 SC (Correction: doubling twice from a start of 33.3 SC). By the test’s end, that particular contract had 75 SC in funds remaining. This means that Sia added 33.3 SC to a contract that had at least 41 SC (Correction: added 66.6 to a contract that had at least 8.4 SC) in remaining, spendable funds.

I also observed instances of Sia making large, unexpected contract purchases. In the worst-case test, while Sia had 1,200 SC sitting in unused contract funds, it suddenly spent its entire 1,766 SC wallet balance on new contracts, even though it already had 1,233 SC sitting in unused contracts.

File replication is bizarre

First, a bit of background on how Sia’s data replication works. Sia stores files redundantly with a 10-of-30 Reed-Solomon encoding. More specifically, it divides each file into chunks of ~40 MiB, then splits each of those chunks into 30 fragments of ~4 MiB each. Sia can reconstruct the original data chunk using any 10 of those 30 fragments. Sia uploads each fragment to a different host so that if any particular host disappears, Sia can still recover the file chunk as long as at least 10 hosts remain online.

Both Sia-UI and Sia’s command-line interface expose replication to the user in terms of a multiplier, like 3x or 3.5x. This multiplier is simply the number of total file fragments uploaded divided by the number of fragments needed to reconstruct the file. A healthy file has a multiplier of 30 / 10 = 3.0x.

If two of the hosts holding fragments go offline, the redundancy will drop to (30 - 2) / 10 = 2.8x. Conversely, redundancy can increase above 3.0x if a host goes offline, then Sia re-uploads its fragment to a new, healthy host, then the original host comes back online. That would result in a redundancy of 31 / 10 = 3.1x.

I calculated aggregate statistics on each file’s redundancy in each of the test cases and found inexplicable numbers:

| Test case | Min Redundancy | Max Redundancy | Median Redundancy | Mean Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worst-case | 3.0x | 11.3x | 5.3x | 5.2x |

| Real data | 0.0x | 5.2x | 2.5x | 2.5x |

| Best-case | 3.0x | 7.3x | 4.1x | 4.0x |

The craziest number is the 11.3x redundancy in the worst-case test. This means that Sia started with 30 fragments of a file, then different hosts disappeared and came back 83 times. That test only had contracts with 60 hosts, so going through this process 83 times seems illogical.

I reported this bug, and the dev team closed it with this note:

Starting from 1.3.2 Sia will only count healthy renewable contracts towards file redundancy. That way we should never see a >3x redundancy for files uploaded with 1.3.2 or higher.

This perhaps prevents users from being confused, but unfortunately doesn’t address the root cause: how could replication have reached such absurdly high levels in the first place?

Also notable from the table is that the real data case shows suspiciously low redundancy. I would expect a handful of files to drop below 3.0x redundancy from time to time. In that test, the median redundancy was 2.5x. This means that most files were in an unhealthy state and hadn’t yet been repaired despite plenty of unspent funds in existing contracts.

Improving load tests

This series of tests was the first rigorous, public test of Sia’s performance. It yielded many interesting findings, but because it was the first of its kind, the test had many shortcomings that I didn’t anticipate when I designed it.

Having gone through the testing process end-to-end, I’d like to share my thoughts on how the Sia community can improve future testing.

Run on cloud servers

I originally designed the tests to run on my home desktop because I wanted to minimize emulation. I was concerned that running the test from a Docker container or VM might introduce unexpected side effects to the test.

I also wanted to test Sia with actual data instead of synthetic files, but that presents challenges in a cloud environment. For example, storing 5 TB of test data on Google Cloud Storage would cost $102.40 per month. On top of that, using Google Compute Engine to run would cost ~$100/TB in bandwidth fees.

Having run the tests on my home infrastructure, I realize that this has significant drawbacks as well. I only have a single desktop, which meant that I had to run the tests serially rather than in parallel. This substantially increased the total duration of these tests. It also meant that my computer usage unrelated to Sia potentially affected the tests. Notably, in the best-case test, my desktop crashed and caused a stark change in Sia’s behavior.

In retrospect, I think that the disadvantages of home infrastructure outweigh its benefits. I recommend that researchers interested in carrying these tests forward run tests from a cloud VPS provider that offers unmetered network bandwidth.

One challenge is that these providers typically don’t provide options for local disks above 1 TB. To work around this, I’ve added a --dataset_copies flag to sia_load_tester. Using this flag, the test operator can tell Sia to cycle through the input files N times. So if you have 50 GiB of files, you can specify --dataset_copies=205 so that sia_load_tester reuploads that file set 205x to simulate 10 TiB of input data.

Bandwidth is a first-class citizen

The biggest metric I failed to account for was bandwidth. I knew I couldn’t measure bandwidth cleanly since I’d be doing other things over the course of the test that competed for bandwidth like downloading files or watching 4K streaming videos on Netflix. So I didn’t give much thought to measuring bandwidth precisely.

I now realize that bandwidth matters a great deal for Sia. Sia has high up-front costs, so it approaches cost-effectiveness after ~1 TB of file data. But a solution that’s inexpensive after 1 TB uploaded is useless if bandwidth is too slow to upload 1 TB in a reasonable amount of time.

There are use-cases that Sia can support if average file upload bandwidth is 100 Mbps that aren’t viable at 50 Mbps. And there are use-cases at 300 Mbps that aren’t viable at 100 Mbps, etc. So, it’s important to measure Sia’s true file data bandwidth so that potential customers understand what Sia can do.

My tests also failed to measure Sia’s bandwidth overhead from non-file activity, such as the overhead of sending operational messages to other Sia peers. Most software deployments are constrained by bandwidth, either by metered costs or limited capacity. If Sia uploads at a file data bandwidth of 5 Mbps but requires 50 Mbps of absolute bandwidth on the wire to achieve that, that’s important for customers to know. Future iterations of this test should measure absolute bandwidth at the network device level to measure Sia’s total bandwidth consumption.

Set more realistic bandwidth minimums

In the test plan, I specified that the test should terminate when Sia stops making upload progress for at least one hour, where “progress” was defined as >= 3 Mbps of absolute bandwidth. This was far too low and tracked the wrong metric.

Instead, the bandwidth minimum should be in terms of file data bandwidth, not absolute bandwidth. Sia could upload at 1 Gbps, but that’s not useful if it’s using the bandwidth just to upload the same file to 11.3x redundancy. File data bandwidth measures what a real consumer cares about: the time it takes to upload their files to Sia.

3 Mbps was also far too low a minimum. At 3 Mbps, it takes 33 days just to upload 1 TB of file data. I can’t imagine any realistic use-case where the consumer would be willing to tolerate a bandwidth so low.

I propose that a more realistic minimum is 50 Mbps of file data bandwidth averaged over the last 24 hours (equivalent to uploading ~500 GiB per day).

Increase file sizes for best-case scenario

One of the surprising outcomes of the load test was that the real data scenario outperformed the worst-case scenario.

It turned out that Sia performed better with a small set of very large files than a large set of ~40 MiB files. A better representation of Sia’s best-case performance would use files that are ~20 GiB each (or, more precisely, 21474693120 bytes so that they’re exactly 512x Sia’s chunk size, maximizing Sia’s file packing efficiency).

Increase file sizes for worst-case scenario

To test Sia’s performance in its worst-case scenario, I uploaded thousands of 1-byte files. It was interesting to see Sia handle this input, but the resulting metrics were so extreme that they’re meaningless.

Some readers gave feedback that performance tests should ignore Sia’s performance on small files and focus only on large files. I think that would be a mistake. It would be like reporting the performance characteristics of a car under the assumption that its minimum speed is 120 mph. That might be the car’s ideal performance speed, but real-world users want to know how it performs in real-world conditions.

There are few practical use-cases where the user has a dataset consisting entirely of immutable files >1 GB in size. Some have suggested that the solution is as easy as building file repacking middleware, but I think such middleware would be more complex than people realize. I’m skeptical that Sia can be cost-effective for any client if they first have to spend several hundred thousand dollars in dev costs to implement their own file repacking layer on top of Sia.

On the other hand, 1-byte files are too extreme. I don’t think any existing cloud provider performs well with such small files.

I propose adjusting the minimum file size to be 4 KB. It’s low enough that it’s representative of Sia as a general-purpose storage solution but not so extreme that metadata and packaging dominate the measurement on Sia or other cloud storage providers.

Automate, automate, automate

The performance tests need to be as automatic as possible. The more that’s automated, the less margin there is for human error and the easier it is for different researchers to reproduce results.

I tried to automate wherever I could, but it’s always difficult to know what needs automating until you follow a process end-to-end. There are two key parts to this test that require more automation: provisioning and analysis.

By provisioning, I mean:

- Installing Sia on the test machine

- Installing test tools on the test machine

- Funding the Sia wallet

- Generating dummy data

I performed these steps manually for each test and documented the commands in the sia_load_tester README, but it would be better to capture this logic in a single script or Ansible playbook (using ansible-role-sia, of course).

The analysis stage also needs better automation for:

- Creating data visualizations from sia_metrics_collector’s output

- Calculating relevant metrics ($/TB, price estimate accuracy, etc.) from the outputs of sia_load_tester and sia_metrics_collector.

For the load test, I created a Google Sheets template to calculate these metrics and create visualizations. That was a passable v1 solution but is not a good long-term solution because it requires the test operator to perform ad-hoc calculations and manually upload CSVs to Google Sheets any time they want to check progress.

A better solution would be a web app that runs on the test system so that the test operator can view the visualizations and stats in their browser in real time as the test progresses.

Why I’m not continuing these tests

I originally conceived of these tests because I considered building a software company on top of Sia. I had a few different ideas for businesses that could capitalize on Sia’s low advertised storage costs, but I needed hard data to understand how Sia performed in the real world.

Having completed the tests, I don’t believe that any of my initial business ideas will be feasible on Sia, so I’m moving on to other projects. I will continue to watch and write about Sia, but I can’t invest the amount of time it takes to perform these tests and analyses.

My side-goal of this testing was to demonstrate the value of metrics. I hope that I’ve achieved this. For Sia to mature, it needs regular, reliable measurement so that the community can understand where the problem areas are. It also shows potential customers what use-cases are feasible and cost-effective on Sia.

There is a group of volunteers discussing a plan for running these tests on an ongoing basis for each new version of Sia. If you’re interested in helping these efforts, email me at michael@spaceduck.io, and I’ll put you in touch with them.

Test plan

I performed this test according to the “Sia Load Test Plan” document that I originally opened for feedback on Feb. 7th, 2018 and finalized on Feb. 14th, 2018.

I ran all tests according to the defined plan with the one exception that I added a maximum time limit of 14 days per test case. I made this amendment after the first test case ran for almost 25 days without making significant upload progress. I wanted to stick to the plan as much as possible to avoid biasing the results, but I worried that letting the test run unbounded would be prohibitively time-consuming and delay results too long.

Test tools

All tools I used in this test are open source, fully documented, and available on Github under the permissive MIT license:

Acknowledgments

Thanks to:

- The Sia bounty fund for providing the Siacoins used in these tests.

- Luke Champine, James Muller, Salvador Herrera for their contributions to the test plan.

- David Vorick for providing feedback about test results.

Corrections

- Sia developer David Vorick corrected my misunderstanding of Sia’s contract renewal strategy. I’ve updated that section with the additional information.